Christ & Gantenbein

Swiss National Museum

best architects 18 in Gold

public buildings

Place

Zurich / Switzerland

Studio

Photos

Walter Mair | Iwan Baan

Description

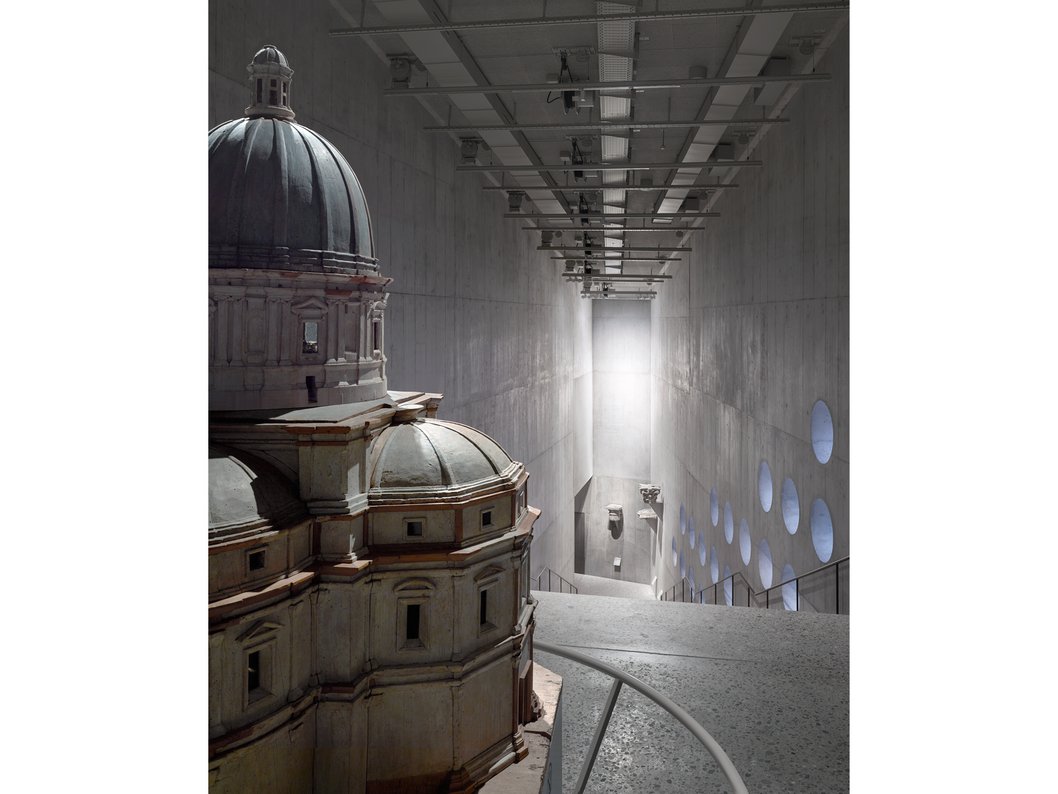

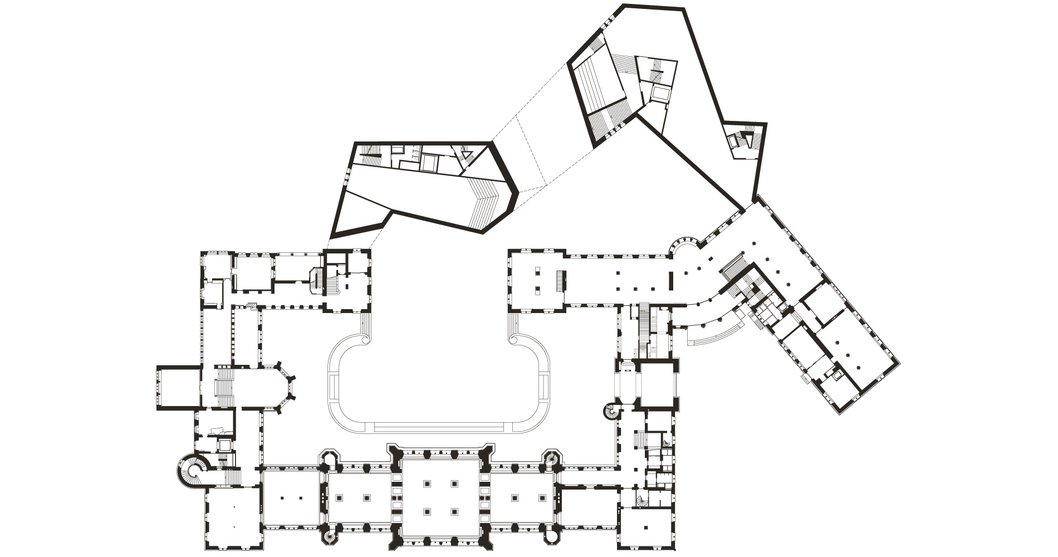

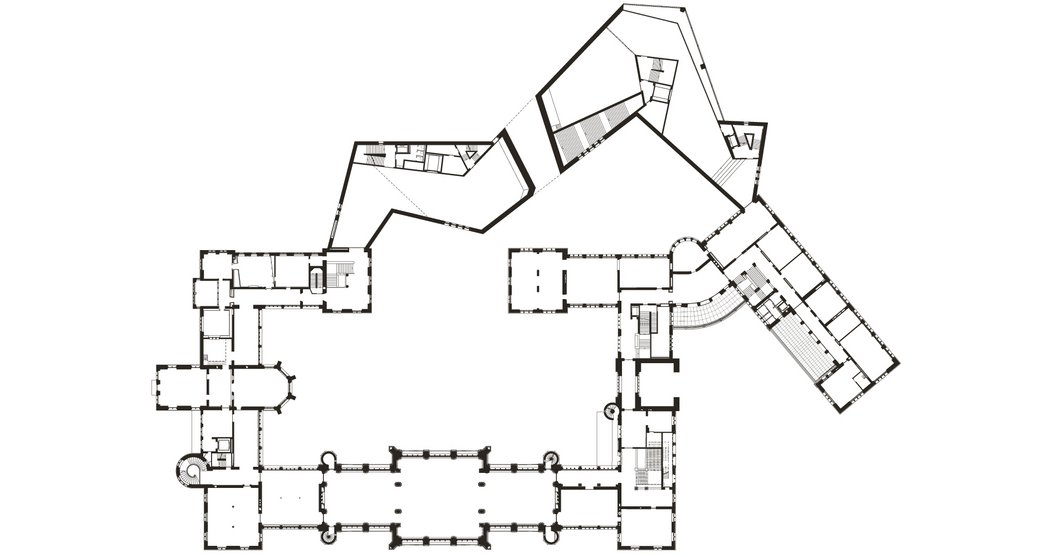

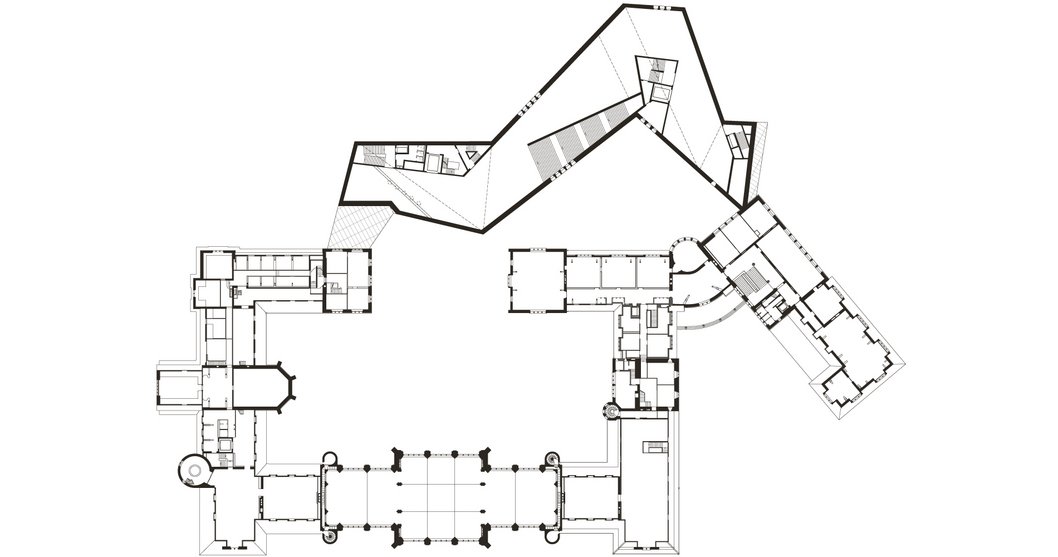

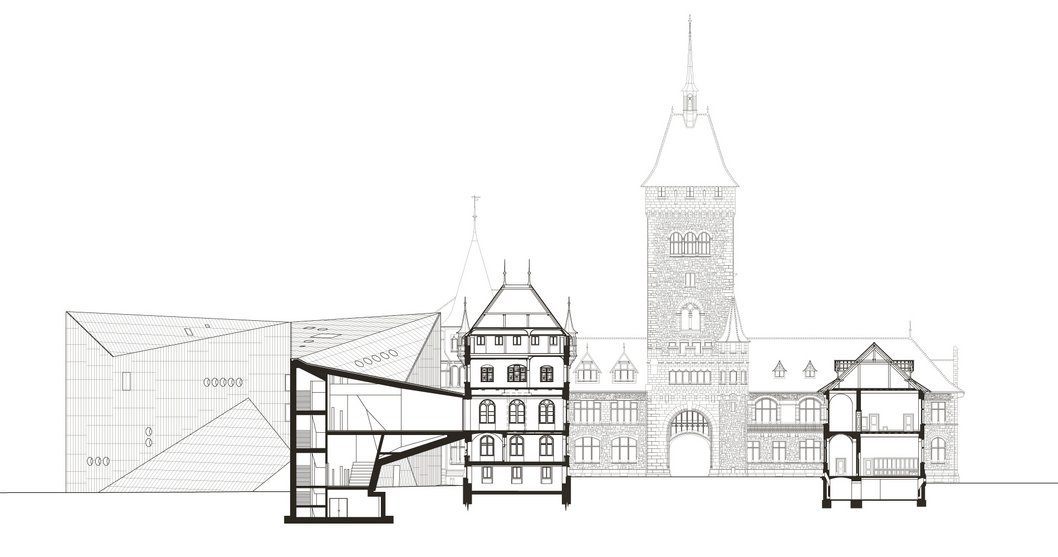

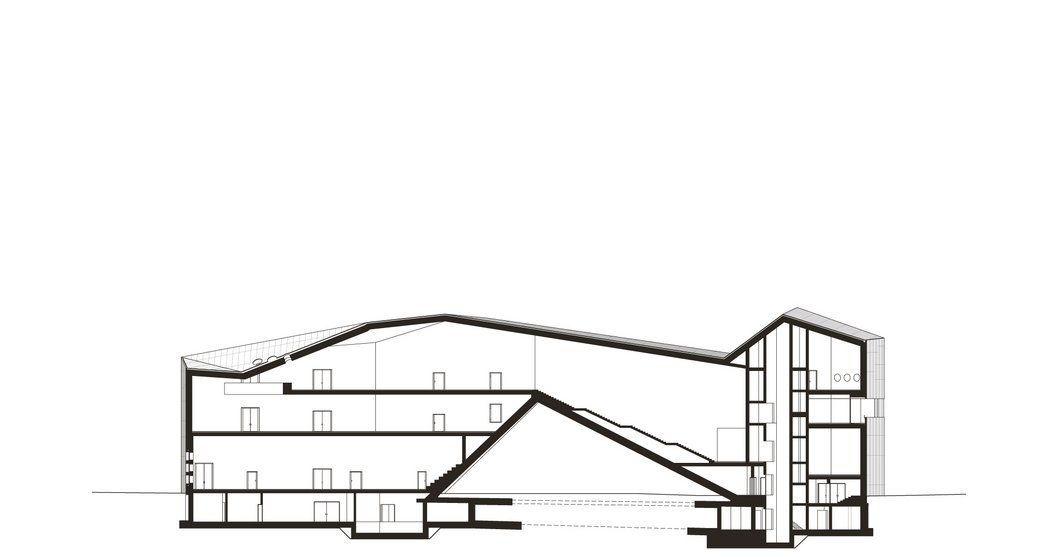

Inaugurated in 1898, the Swiss National Museum was conceived as an eccentric architectural collage charged with celebrating the newly born and multifaceted federalist state. A bit more than a century later, its original layout had become outdated. Christ & Gantenbein won the international competition to realise the museum’s extension located in the city centre near the main train station. The proposal acknowledges the assemblage principle and doesn’t take sides with ideal architecture. Closing the existing buildings’ U-shaped perimeter, the new volume takes the shape of a dramatically bent bridge that allows visitors to experience the exhibitions along a non-interrupted path but leaves the access from the courtyard to the neighbouring Platzspitz Park open.

Since »now« is not the end of history but only a stepping stone between the past and the future, the architecture that we build today has to meet current criteria, but also engage with the past and point to the future.

The extension offers flexible exhibition spaces, a study centre with library and a large auditorium. The design managed to create a unity between old and new through the reinterpretation of existing architectural motifs: the origami-like roof landscape of the extension evokes the wild pitched-roofs composition of the original, while the double wall construction of the new wing is as thick as the 19th-century walls while fulfilling contemporary energy-saving standards. The characteristic colour of the old building’s tuff façade is matched in the extension through the addition of a tuff aggregate to the concrete.

christ & gantenbein

We strive day after day to develop strong projects with staying power: contemporary, functional and specific buildings – able to inspire a sense of universal meaning and timelessness – whose physical reality, construction methods and materials are rock solid. We want these spaces to be open to future uses that we cannot yet begin to imagine, expressing an architectonic language that says more about architecture in general than about our own interests.